Munish Sood

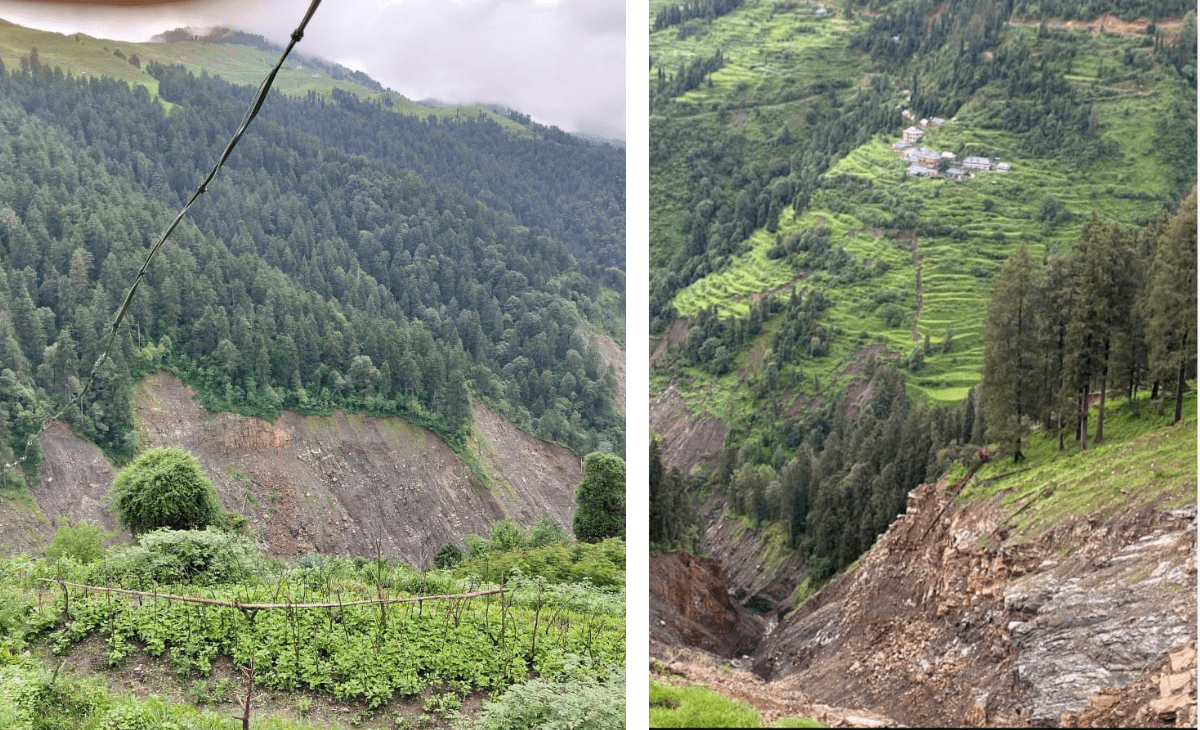

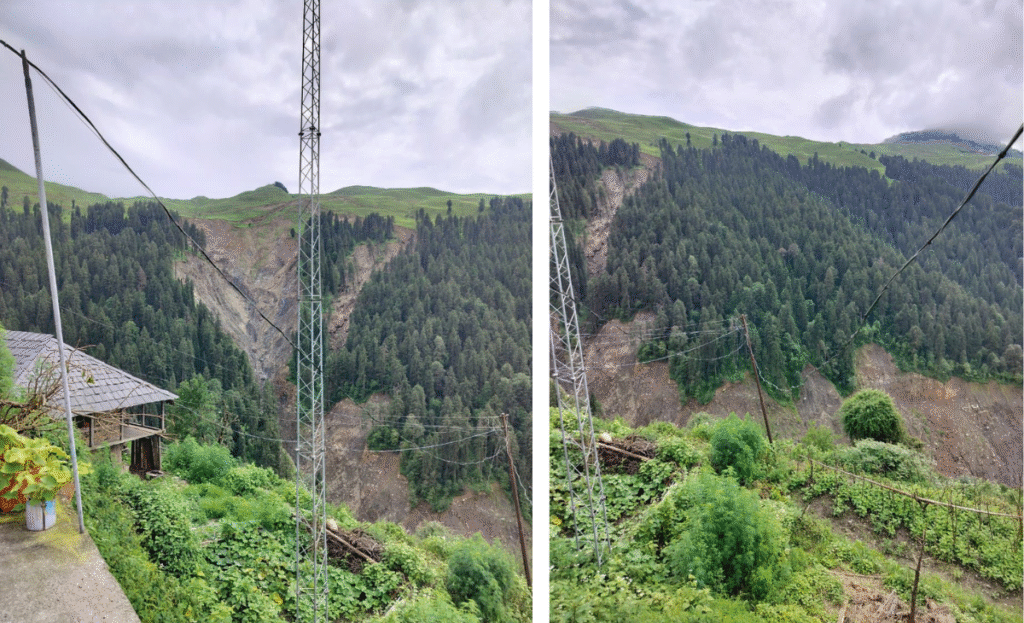

MANDI: A slow-moving disaster is silently devouring Kalang village, nestled near the famous Prashar Lake in Himachal Pradesh’s Mandi district. Once a picturesque hill village, Kalang is now crumbling, physically and emotionally. The land is sinking, houses are developing cracks, fields are splitting and the fear of a complete collapse looms large over the community.

In the latest and most serious development, 14 families have been relocated by the district administration as land cracks widen and hills continue to slide due to intense monsoon activity. The authorities have declared the area unsafe for habitation, underscoring the urgent need for long-term rehabilitation and deeper reflection on the fragile state of Himalayan ecology.

Difficult to sleep at night, say villagers

“This time, the land behind our homes is sliding fast and wide cracks have appeared in the fields,” said Raj Thakur, a resident whose family has lived in Kalang for generations. “We don’t know if our village will survive another monsoon.”

What’s unfolding now is not a sudden disaster but the culmination of over a decade of slow, relentless land movement. Since 2013, villagers have reported widening fissures and sinking terrain. By 2024, three homes became unlivable and had to be abandoned. A primary school has already been lost to the erosion. Over 100 bighas of cultivable land has turned into unstable rubble.

“The soil here is no longer trustworthy,” said another local, his voice shaking. “We are still alive, but our village is dying.”

Temporary relief, permanent questions

In response to the escalating danger, the Mandi district administration has shifted the affected families to temporary camps with 17 tents, pitched on government-owned land. Electricity and water arrangements are being expedited. Additional District Magistrate Madan Kumar said, “The safety of residents is our top priority.” But villagers say the move only delays a deeper tragedy unless permanent rehabilitation and ecological restoration are initiated.

“We’ve been warning officials since 2014,” said Chhape Ram, vice-pradhan of the local panchayat. “Only now, when the land has literally started falling apart, has action begun. It’s too little, too late.”

Nature’s wrath and gaps in state policy

The landslide-prone region has long been vulnerable to extreme weather, but climate change and human interference have worsened the situation. In 2023, the nearby Bagi stream swelled uncontrollably, and a key bridge collapsed due to a landslide upstream, originating from the same hills that threaten Kalang today.

Following is the list of the families displaced (head of family)

- Bhiniri Singh, S/o Balaram

- Lal Singh, S/o Balaram

- Prem Singh (80), S/o Narataru

- Kum Dev (81), S/o Narataru

- Rajan (50), S/o Daulat Ram

- Yadav Singh (51) S/o Tek Chand

- Ram Litte (29) S/o Balimandar

- Chandramani (51)

- Jagdish (52)

- Ramesh Kumar S/o Ved Ram

- Man Singh (51)

- Kalidevi W/o Balaram

- Jaspal S/o Dr Daulat Ram

Environmental experts have blamed irregular and heavy monsoons, deforestation, unscientific road construction and poor geological surveys. “This is not an isolated event. The Himalayas are shouting at us — and we are still not listening,” said a senior environmentalist from IIT-Mandi.

“Kalang is only one of the several villages across the Himalayan region now facing existential threats. But it may also serve as a wake-up call for national policymakers, climate planners and disaster management agencies,” said the environmentalist.

Immediate demands from the village include declaration of Kalang as a landslide-danger zone, permanent rehabilitation of displaced families, installation of early warning systems, scientific land-use planning for the region and large-scale reforestation and slope stabilisation.

“As the nation watches disasters unfold in Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Himachal year after year, Kalang is a reminder that these are not isolated accidents. They are warning signs. And the longer we wait to respond, the more lives and land we will lose,” said the environmentalist.